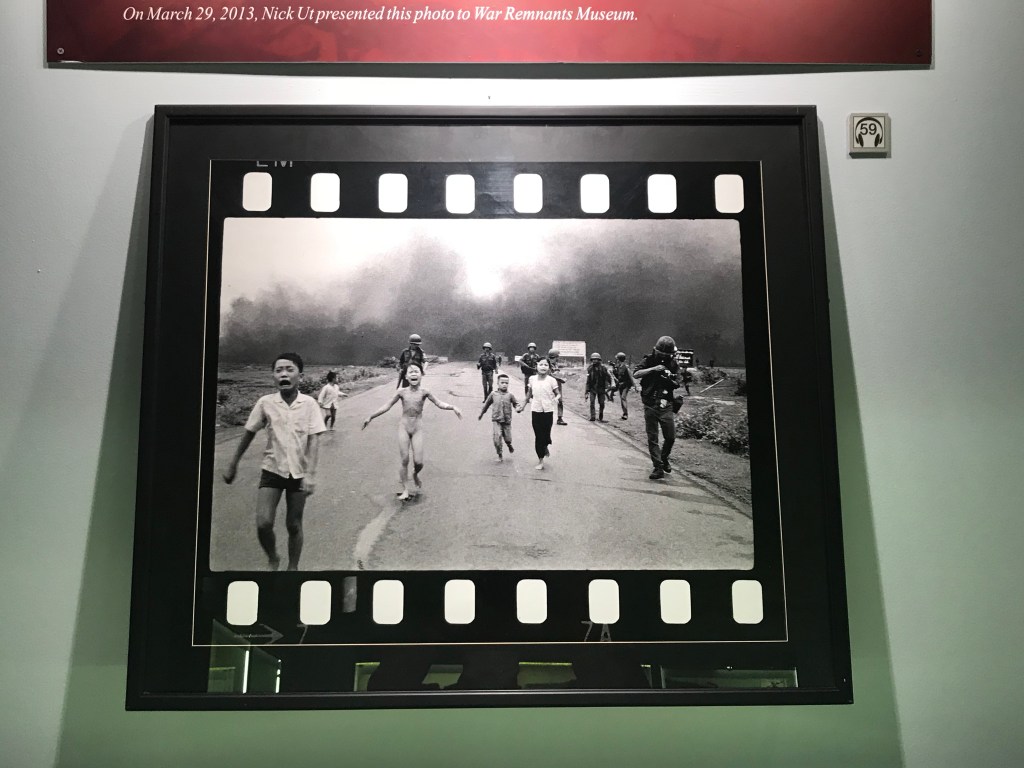

Ho Chi Minh City’s most profoundly emotional collection is displayed at its War Remnants Museum, where visitors learn more than they wanted about what is called the American War.

Pham Anh Dao, 70, gestured toward his left foot, or what should have been his left foot. Now, there was merely a knob, a long-ago memory of a field medic’s emergency handiwork. The American War had already ended, Dao told me, when he stepped on a land mine in the jungles of Vietnam’s Central Highlands. He was lucky. He survived.

Dao’s story is hardly unique. The war that the United States waged in Southeast Asia between 1965 and 1975 took a terrible toll. Yes, more than 47,000 Americans died; but so did over 1.5 million Vietnamese, including at least 350,000 civilians. (Casualty figures are estimates.) And those are only the dead.

In most of the rest of the world, it is not widely recognized that this is a war that has kept on giving — or, more accurately, kept on taking away. (Known in the U.S. as the Vietnam War, it is the American War in Vietnam.) The conflict left a legacy of unexploded ordnance as well as hereditary illness and birth defects caused by Agent Orange and other chemical defoliants.

A Day at the Museum

For me, that’s the biggest takeaway from a visit to the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City. (Another War Remnants Museum is in Hanoi.) I consider it the single most important urban attraction for Western tourists.

Located just a couple of streets north of Independence Palace, where South Vietnam surrendered to North Vietnam in 1975, the Ho Chi Minh City museum is a rude reminder to Western visitors that the Americans didn’t play nice. During a war, of course, no one plays nice, and the account rendered here is an undeniably biased one. But it’s hard to look at graphic photographs of atrocities like the notorious My Lai massacre or the Agent Orange attacks, whose victims still haunt Vietnam’s streets.

Visitors arrive at the museum through a curated display of captured U.S. tanks, warplanes and artillery (including an M132 flamethrower) in the museum yard, presented side-by-side with Vietnamese equipment. Nearby, a replica prison recalls such punishments as a notorious isolation chamber (the “tiger cage”) and a guillotine from the French colonial era.

War Crimes and Chemicals

Exhibits within the museum are on three floors, with interpretive signs in English, French and Vietnamese. On the ground floor are well-documented testimonies by U.S. servicemen who could not keep silent about war atrocities after they returned home.

One level up, some of the frightening images that illustrate “War Crimes” may be all too familiar to older Americans who recall the carnage of My Lai, Son My and Pleiku. A collection of U.S. Army weapons is displayed for its role in the “persecution, torture, murder and massacre; bombing innocent peoples’ homes, villages, hospitals, schools, causing casualty and damage to Vietnamese people.”

Other rooms on the same floor describe, in words and pictures, the disabling efffects of Agent Orange and related dioxins. Panels of photographs looked like something from a freak show. As many as 3 million Vietnamese suffered disfiguring wounds or illnesses as a result of exposure to the chemicals. Third and even fourth generations of victims still show genetic disabilities; the International Red Cross estimates that as many as 1 million people may still have health problems as a result of the dumping of Agent Orange prior to 1975.

Historical Truths

On the top floor of the museum, an informative display labeled “Historical Truths” lays out the roots of the American War, beginning with communist Vietnam’s 1945 declaration of independence from colonial France and its subsequent war with the Europeans. That ended with a final victory in 1954 at Dien Bien Phu, on the border of Laos in North Vietnam. The U.S. almost immediately involved itself by providing financial aid and military advisers to the democratic government of South Vietnam. The Americans crossed the thin red line when Marines landed at Da Nang in 1965. The next 10 years were ugly.

In “Requiem,” I found a collection of more than 200 photos by (and of) 133 war correspondents from 11 countries who died doing their jobs in Vietnam. As a journalist myself, I found this particularly poignant. Indeed, in my earliest years in the business, in the early 1970s, I had brief conversations with a couple of the men pictured here. Journalist Carl Robinson, who lived in South Vietnam from 1964 to 1975, is a personal friend.

Unexploded Ordnance

An exhibit on unexploded ordnance brought me back to my conversation with Pham Anh Dao. Since the war ended 46 years ago, the detonation of land mines, bombs, mortars and grenades has killed more than 40,000 people in Vietnam and adjacent Cambodia and Laos. The ordnance still takes several hundred lives a year — often innocent people planting rice or tilling their gardens.

Gratefully, the U.S. government has spent more than $65 million in the past 20-plus years to clear ordnance, and nonprofit organizations like Seattle-based PeaceTrees Vietnam have done their part. But rural areas, especially the central provinces, may remain hazardous for many more decades. I’ll be especially cautious when I wander from the beaten path, lest I suffer an injury like my friend Dao … or worse.

Next: A visit to Phu Quoc island