Through periods of freedom and suppression, Vietnamese art continues to make an impression as it reveals culture and history to a curious world.

If art is too tightly controlled, it is not art. Like music or literature, the fine arts of painting and sculpture must be creatively manifested or their meaning is lost. Individual expression is paramount; inspiration is essential.

There is no greater indicator of a culture’s freedom — political freedom, religious freedom, socioeconomic freedom — than in the works that its artists generate. One can perhaps suggest a theme to a painter, but one cannot direct how the work should be done.

I thought about this as I looked at many of the modern works in The Vietnam Fine Arts Museum in Hanoi. With very little guesswork, I could extrapolate the main bullet points (no pun intended) of the past 150-odd years of the country’s turbulent history: The French colonial influence was succeeded by the redirection of the revolutionary north, the tightly controlled autocracy since reunification, and finally, the slow reemergence of more liberated art under Western economic stimulus, particularly in Ho Chi Minh City (the former Saigon).

There were artists in what is now Vietnam as long ago as 10,000 years, as indicated by clay pottery unearthed in prehistoric digs in the far north. By about 3,000 years ago, decorative touches could be seen in Neolithic pottery and ceramics. Elaborate bronze drums from the Đông Sơn Culture were elaborately decorated with geometric patterns and depictions of lifestyle scenes, from wardrobe to farming practices.

Even during long periods of Chinese dominance and the absorption of a Confucian-Taoist ethic, Vietnamese art retained many distinctive characteristics. These were best seen in ceramic art, where traditional styles melded with those of China’s Tang and Song dynasties. Ceramics of the 11th- and 12th-century Lý Dynasty became famous across Asia. The 19th-century Nguyen Dynasty, the last imperial rulers of Vietnam, saw a renewed interest in ceramics and porcelain art.

Before French colonization, Vietnamese art was mostly religious, ranging from paintings and ceramics to lacquered furniture that adorned pagodas and temples. European influence arrived in the 1860s. In establishing the Ecole de Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine (School of Fine Arts of Indochina) in 1925, the French began teaching Western art history and aesthetic techniques such as linear perspective, modeling in the round, and plein air — that is, moving the canvas outdoors where students could incorporate landscapes and the cultural environment.

A leading artist of this period was To Ngoc Van, who became known for a “poetic reality” style that idealized femininity, sometimes merging religion and mythology with nostalgic romanticism. But he abandoned this style with Ho Chi Minh’s 1945 declaration of Vietnamese independence from both the French and their Second World War Japanese overlords. To immersed himself in revolutionary rhetoric, leading resistance artists to the Viet Minh encampment in the hills of Tay Bac, where they built a new art school.

To Ngoc Van now embraced modern realism. Art, he said, must inspire the revolution, appealing to — and educating — the Vietnamese people. Artists under his tutelage created images of heroic battle scenes, portraits of peasants supporting the soldiers, pictures of the glorious countryside. To himself died in 1954 of injuries he suffered during the climactic battle of Dien Bien Phu.

Now rid of the French, the Vietnamese Communist party was able to solidify its control of the north before having to counter the American threat beginning in the mid-1960s. That meant restricting the freedom of expression. Although many writers and artists demanded more liberty, at least two art and literary journals were banned for supporting this viewpoint in the 1950s.

After the National Arts Association was established in 1956, only its 108 members could exhibit or sell their works, mainly propaganda poster designs and illustrations. Private galleries were banned, preventing any non-members from displaying their work.

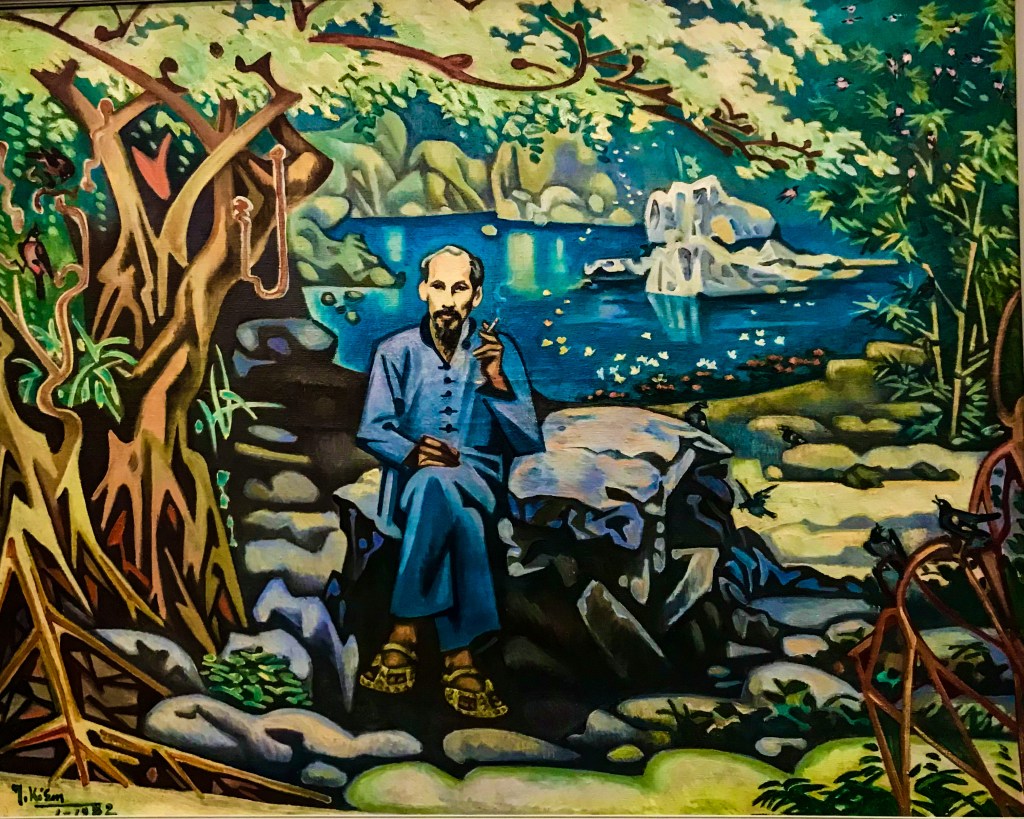

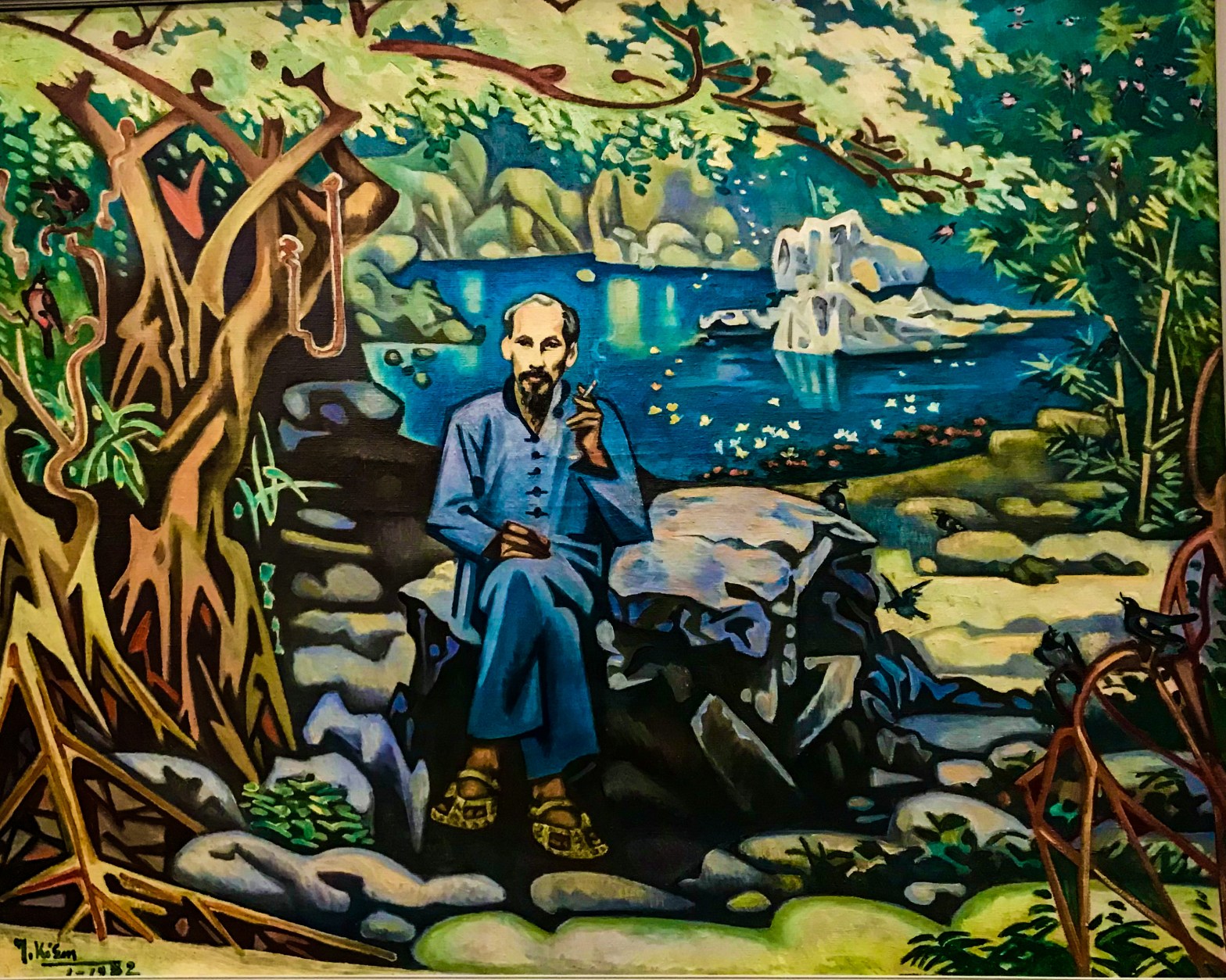

Strict guidelines declared that subject matter should have a “national character,” which usually meant the countryside, a battle scene, or a portrait of Uncle Ho. Nonetheless, most work continued to rely upon detachment and a classic realist perspective, while like oil painting itself had been introduced by the Europeans — even as all works were now renamed “national.”

Unsurprisingly, individualism and freedom of expression persisted much longer in the republican south than in the north. After Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel by the Geneva Conference of 1954, many northern artists fled to Saigon. Until the fall of the city in 1975 — and many artists were sent for “re-education” — they experimented with abstraction and other contemporary expressions.

An economic reform in 1986 claimed to allow artists a greater outlet for creative expressions, even as the government censured a workshop: “The retreat not only promoted individual expression and art for art’s sake,” a government-controlled newspaper explained. “It also went against what the state had instituted over the past three decades in that it allowed artists to explore their individuality rather than represent collective sentiments of their community.”

Today, due in part to the purchasing power of foreign tourists, the pendulum shows signs of reversing its direction, especially in Ho Chi Minh City (the former Saigon). Public galleries exhibit works in oil, acrylic and lacquer (on wood) — many of them expert copies of older paintings, but featuring a significant number of originals. As well, a younger generation of Vietnamese artists is active in more contemporary styles, including installation art, video art and performance art.

Prestigious RMIT University Vietnam, an affiliate of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, is a leader in modern Vietnamese art. Its collection, exhibited in HCMC District 7, is considered among the finest in the world, including both established and mid-career artists along with emerging talents. Indeed, RMIT has become a shining light for creative expression among young Vietnamese.

I hope it’s a place where young Mina Anh Tri might someplace dream of going. This young girl, only 8 years old, nervously opened her artist’s notebook to me in an English-language class that I teach — and I was flabbergasted. With no formal art training, she has captured both rural and urban visions of a modern child’s life in vibrant color, even if her figures are imperfect.

Or perhaps they are perfect. It is individual expression, of course, and as Westerners have long opined, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. I think it’s beautiful.

Where to find art: In Hanoi, The Vietnam Fine Arts Museum is located at 66 Nguyen Thai Hoc in the Ba Dinh district. In Ho Chi Minh City, the Fine Arts Museum is at 97A Pho Duc Chinh, not far from Bến Thành market in District 1. The RMIT University collection may be visited at 702 Nguyễn Văn Linh, Tân Hưng, District 7, Ho Chi Minh City.

Thank you John.

LikeLike